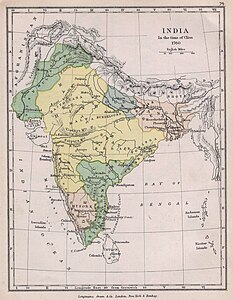

Con il termine di Raj della Compagnia o Company Raj si indica l'insieme di domini diretti e protettorati che il Regno Unito accumulò e organizzò nel subcontinente indiano attraverso la Compagnia britannica delle Indie Orientali nella prima fase del colonialismo britannico in India.

Storia

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Il colonialismo britannico in India ebbe inizio nel 1757 quando, dopo la Battaglia di Plassey il Nawwāb del Bengala si arrese e consegnò i suoi domini alla Compagnia delle Indie Orientali.[1] A partire dal 1765 alla Compagnia fu garantito il diritto di raccogliere imposte nell'area del Bengala e del Bihar,[2] e nel 1772 la capitale di questi nuovi domini venne posta a Calcutta e venne nominato il primo Governatore Generale nella persona di Warren Hastings.[3] Il governo della Compagnia perdurò sino al 1858 quando, dopo i Moti indiani del 1857 il governo britannico decise di assumere direttamente il controllo e l'amministrazione dell'India con la costituzione del British Raj.

Espansione e territorio

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]La Compagnia inglese delle Indie Orientali fu fondata nel 1600 col nome di The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies. Essa approdò per la prima volta in India nel 1612 dopo che l'Imperatore mughal Jahangir gli ebbe garantito il diritto di fondare sul suolo indiano una struttura con annesso porto commerciale presso Surat sulla costa occidentale. Nel 1640, dopo aver ricevuto un permesso simile dall'Imperatore Vijayanagara, fu fondata una seconda struttura a Madras nella costa sud-orientale. L'isola di Bombay, non lontana da Surat e già possedimento portoghese, venne portata in dote al Regno d'Inghilterra dopo il matrimonio tra Caterina di Braganza e Carlo II d'Inghilterra e concessa poi alla Compagnia nel 1668. Vent'anni dopo, la Compagnia stabilì una nuova struttura a Calcutta presso il fiume Gange. Nello stesso tempo altre compagnie vennero fondate da parte di altri Stati europei interessati al colonialismo come Portogallo, Paesi Bassi, Francia e Danimarca.

La Compagnia aveva de facto il controllo diretto su diverse regioni dell'India, ma tali domini non furono ufficialmente indipendenti dall'Impero indiano sino alla vittoria di Robert Clive nel 1757 nella Battaglia di Plassey. Un'altra vittoria importante fu quella del 1764 nella Battaglia di Buxar (nel Bihar), che consolidò il potere della compagnia e forzò l'imperatore Shah 'Alam II a nominare diwan delle regioni del Bengala, del Bihar e di Orissa un rappresentante della compagnia. In questo modo la Compagnia divenne la reggente dell'area gangetica, intensificando la propria influenza a Bombay e Madras. Le Guerre anglo-mysore (1766–1799) e le Guerre anglo-maratha (1772–1818) consentirono alla Compagnia di prendere il controllo di tutto il sud dell'India.

La proliferazione dei territori della Compagnia ebbe due risvolti: il primo consisteva nell'acquisire territori degli Stati indigeni e porli sotto il proprio diretto controllo. Così fu per le regioni del Rohilkhand, di Gorakhpur, del Doab (1801), di Delhi (1803) e del Sindh (1843). Punjab, Province nord-occidentali e Kashmir furono annessi solo dopo la Seconda guerra anglo-sikh del 1849, mentre il Kashmir fu immediatamente venduto, secondo i termini dettati dal Trattato di Amritsar del 1846, alla dinastia Dogra di Jammu, e divenne così uno Stato principesco indipendente. Nel 1854 la provincia di Berar fu annessa ai domini della Compagnia e lo Stato di Awadh (Oudh per i Britannici) ebbe eguale sorte due anni più tardi.[4]

La seconda forma di acquisizione del potere da parte della Compagnia era essenzialmente dovuta ad una grande autonomia interna. Dal momento che la Compagnia era sostenitrice innanzitutto di operazioni finanziarie, essa poteva contare su propri finanziamenti che le "imponevano" di stabilire un certo controllo sulle aree produttive.[5] Fondamentali furono in questo senso gli accordi trovati con i diversi principi indigeni i quali - qualora avessero voluto entrare in relazione con la compagnia per esportare i propri prodotti con rendite moltiplicate dal grande commercio britannico - dovevano concedere diritti "politici" alla Compagnia su determinate aree produttive.[6] In cambio, la Compagnia proponeva anche la difesa militare del territorio stesso, nel rispetto delle tradizioni locali.[6] Tra gli Stati con cui la compagnia strinse patti di alleanza ricordiamo: Cochin (1791), Jaipur (1794), Travancore (1795), Hyderābād (1798), Mysore (1799), Stati collinari del Sutlej meridionale[7] (1815), Agenzia dell'India Centrale (1819), Kutch e Gujarat Gaikwad (1819), Rajputana (1818) e Bahawalpur (1833).[4]

Governatori generali

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Note

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]- ^ Bose Jalal, 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Brown, 1994, p. 46, Peers, 2006, p. 30

- ^ Metcalf Metcalf, p. 56.

- ^ a b Ludden, 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Brown, 1994, p. 67.

- ^ a b Brown, 1994, p. 68.

- ^ Stati della regione del Punjab del XIX secolo che si estendevano tra il fiume Sutlej a nord, l'Himalaya a est, il fiume Yamuna e il Distretto di Delhi a sud e il Distretto di Sirsa a ovest.

Bibliografia

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]- Sekhar Bandyopadhyay, From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India[collegamento interrotto], New Delhi and London: Orient Longmans. Pp. xx, 548., 2004, ISBN 81-250-2596-0.

- Sugata Bose e Ayesha Jalal, Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, London and New York: Routledge, 2nd edition. Pp. xiii, 304, 2003, ISBN 0-415-30787-2.

- Judith M. Brown, Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. xiii, 474, 1994, ISBN 0-19-873113-2. URL consultato l'8 aprile 2011 (archiviato dall'url originale il 3 ottobre 2008).

- Dennis Judd, The Lion and the Tiger: The Rise and Fall of the British Raj, 1600–1947, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. xiii, 280, 2004, ISBN 0-19-280358-1 (archiviato dall'url originale il 27 marzo 2008).

- Hermann Kulke e Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, 4th edition. Routledge, Pp. xii, 448, 2004, ISBN 0-415-32920-5.

- David Ludden, India And South Asia: A Short History, Oxford: Oneworld Publications. Pp. xii, 306, 2002, ISBN 1-85168-237-6. URL consultato l'8 aprile 2011 (archiviato dall'url originale il 16 luglio 2011).

- Claude (ed) Markovits, A History of Modern India 1480–1950 (Anthem South Asian Studies), Anthem Press. Pp. 607, 2005, ISBN 1-84331-152-6.

- Barbara Metcalf e Thomas R. Metcalf, A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xxxiii, 372, 2006, ISBN 0-521-68225-8.

- Douglas M. Peers, India under Colonial Rule 1700–1885, Harlow and London: Pearson Longmans. Pp. xvi, 163, 2006, ISBN 0-582-31738-X.

- Peter Robb, A History of India (Palgrave Essential Histories), Houndmills, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. xiv, 344, 2004, ISBN 0-333-69129-6.

- Percival Spear, A History of India, Volume 2, New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. Pp. 298, 1990, ISBN 0-14-013836-6.

- Burton Stein, A History of India, New Delhi and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. xiv, 432, 2001, ISBN 0-19-565446-3.

- Stanley Wolpert, A New History of India, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 544, 2003, ISBN 0-19-516678-7.

- Clare Anderson, Indian Uprising of 1857–8: Prisons, Prisoners and Rebellion, New York: Anthem Press, Pp. 217, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84331-249-9. URL consultato l'8 aprile 2011 (archiviato dall'url originale l'11 febbraio 2009).

- C. A. Bayly, Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire (The New Cambridge History of India), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 248, 1990, ISBN 0-521-38650-0.

- C. A. Bayly, Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780–1870 (Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 426, 2000, ISBN 0-521-66360-1.

- Sumit Bose, Peasant Labour and Colonial Capital: Rural Bengal since 1770 (New Cambridge History of India), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press., 1993.

- Rajnarayan Chandavarkar, Imperial Power and Popular Politics: Class, Resistance and the State in India, 1850–1950, (Cambridge Studies in Indian History & Society). Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 400, 1998, ISBN 0-521-59692-0.

- D. A. Farnie, The English Cotton Industry and the World Market, 1815–1896, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Pp. 414, 1979, ISBN 0-19-822478-8.

- R. Guha, A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of the Permanent Settlement, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-59692-0.

- P. J. Marshall, Bengal: The British Bridgehead, Eastern India, 1740–1828, Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- P. J. Marshall, The Making and Unmaking of Empires: Britain, India, and America c.1750–1783, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 400, 2007, ISBN 0-19-922666-0. URL consultato l'8 aprile 2011 (archiviato dall'url originale il 25 maggio 2011).

- Thomas R. Metcalf, The Aftermath of Revolt: India, 1857–1870, Riverdale Co. Pub. Pp. 352, 1991, ISBN 81-85054-99-1.

- Thomas R. Metcalf, Ideologies of the Raj, Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press, Pp. 256, 1997, ISBN 0-521-58937-1.

- Maria Misra, Business, Race, and Politics in British India, c.1850–1860, Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. 264, 1999, ISBN 0-19-820711-5.

- Andrew (ed.) Porter, Oxford History of the British Empire: Nineteenth Century, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 800, 2001, ISBN 0-19-924678-5.

- Eric Stokes e C.A. Bayly (ed.), The Peasant Armed: The Indian Revolt of 1857, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986, p. 280, ISBN 0-19-821570-3.

- Ian Stone, Canal Irrigation in British India: Perspectives on Technological Change in a Peasant Economy (Cambridge South Asian Studies), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 392, 2002, ISBN 0-521-52663-9.

- B. R. Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970 (The New Cambridge History of India, III.3), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press., 1993.

- Robert Travers, Ideology and Empire in Eighteenth-Century India: The British in Bengal (Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society)[collegamento interrotto], 2007, ISBN 0-521-05003-0.

- Jayant Banthia e Tim Dyson, Smallpox in Nineteenth-Century India, in Population and Development Review, vol. 25, n. 4, 1999, pp. 649–689.

- John C. Caldwell, Malthus and the Less Developed World: The Pivotal Role of India, in Population and Development Review, vol. 24, n. 4, 1998, pp. 675–696.

- Richard Drayton, Science, Medicine, and the British Empire, in Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 264–276, ISBN 0-19-924680-7.

- Robert E. Frykenberg, India to 1858, in Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 194–213, ISBN 0-19-924680-7.

- Peter Harnetty, 'Deindustrialization' Revisited: The Handloom Weavers of the Central Provinces of India, c. 1800–1947, in Modern Asian Studies, vol. 25, n. 3, 1991, pp. 455–510.

- Gad Heuman, Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Abolition, in Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 315–326, ISBN 0-19-924680-7.

- Ira Klein, Plague, Policy and Popular Unrest in British India, in Modern Asian Studies, vol. 22, n. 4, 1988, pp. 723–755.

- Ira Klein, Materialism, Mutiny and Modernization in British India, in Modern Asian Studies, vol. 34, n. 3, 2000, pp. 545–580.

- Robert Kubicek, British Expansion, Empire, and Technological Change, in Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 247–269, ISBN 0-19-924678-5.

- Kapil Raj, Colonial Encounters and the Forging of New Knowledge and National Identities: Great Britain and India, 1760–1850, in Osiris, 2nd Series, vol. 15, Nature and Empire: Science and the Colonial Enterprise, 2000, pp. 119–134.

- Rajat Kanta Ray, Asian Capital in the Age of European Domination: The Rise of the Bazaar, 1800–1914, in Modern Asian Studies, vol. 29, n. 3, 1995, pp. 449–554.

- Tirthankar Roy, Economic History and Modern India: Redefining the Link, in The Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 16, n. 3, 2002, pp. 109–130.

- B. R. Tomlinson, Economics and Empire: The Periphery and the Imperial Economy, in Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 53–74, ISBN 0-19-924678-5.

- D. A. Washbrook, India, 1818–1860: The Two Faces of Colonialism, in Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 395–421, ISBN 0-19-924678-5.

- Diana Wylie, Disease, Diet, and Gender: Late Twentieth Century Perspectives on Empire, in Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 277–289, ISBN 0-19-924680-7.

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV, The Indian Empire, Administrative, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552., 1908.

- R. C. Majumdar, H. C. Raychaudhuri e Kalikinkar Datta, An Advanced History of India, London: Macmillan and Company Limited. 2nd edition. Pp. xiii, 1122, 7 maps, 5 coloured maps., 1950.

- Horace H Wilson, The History of British India from 1805 to 1835, London: James Madden and Co., 1845, OCLC 63943320.

- Vincent A. Smith, India in the British Period: Being Part III of the Oxford History of India, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press. 2nd edition. Pp. xxiv, 316 (469-784), 1921.

- India from Congress

- Pakistan from Congress

Altri progetti

[modifica | modifica wikitesto] Wikimedia Commons contiene immagini o altri file su Company Raj

Wikimedia Commons contiene immagini o altri file su Company Raj