| Coronavirus umano 229E | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Dominio | Acytota |

| Ordine | Nidovirales |

| Famiglia | Coronaviridae |

| Genere | Alphacoronavirus |

| Sottogenere | Duvinacovirus |

| Nomi comuni | |

|

HCoV-229E | |

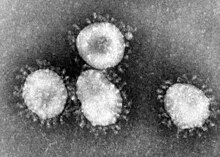

Il coronavirus umano 229E (HCoV-229E) è una specie di coronavirus che infetta l'uomo e i pipistrelli.[1] La specie appartiene al genere Alphacoronavirus ed è l'unica del sottogenere Duvinacovirus.[2][3]

È un virus a RNA avvolto a senso positivo, a singolo filamento, che entra nella sua cellula ospite legandosi al recettore APN.[4]

Insieme al coronavirus umano OC43 è uno dei virus responsabili del raffreddore comune,[5][6] ed è uno dei sette coronavirus umani (che includono HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-1 e SARS-CoV-2) distribuiti a livello globale.[7][8]

Trasmissione

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]HCoV-229E si trasmette attraverso le goccioline respiratorie e i fomiti.

Sintomi

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]HCoV-229E è associato a una serie di sintomi respiratori, che vanno dal comune raffreddore agli esiti ad alta morbilità come la polmonite e la bronchiolite. Tuttavia, tali esiti di morbilità così elevata sono sempre osservati in casi con coinfezione con altri agenti patogeni respiratori con un'unica eccezione segnalata; sebbene l'infezione con 229E da solo sia quasi esclusivamente associata a malattia asintomatica o lieve, ad oggi esiste un singolo caso clinico pubblicato di infezione da 229E che ha causato la sindrome da distress respiratorio acuto (ARDS) in un paziente altrimenti sano, senza coinfezione rilevabile con un altro patogeno.[9] HCoV-229E è anche uno dei coronavirus più frequentemente codificati con altri virus respiratori, in particolare con il virus respiratorio sinciziale umano (HRSV).[10][11][12] Tuttavia i virus sono stati rilevati in diverse parti del mondo in diversi periodi dell'anno.[13][14][15]

Note

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]- ^ Yvonne Xinyi Lim, Yan Ling Ng e James P. Tam, Human Coronaviruses: A Review of Virus–Host Interactions, in Diseases, vol. 4, n. 3, 25 luglio 2016, p. 26, DOI:10.3390/diseases4030026, ISSN 2079-9721, PMID 28933406.«See Table 1.»

- ^ (EN) Virus Taxonomy: 2018 Release, su International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), October 2018. URL consultato il 13 January 2019.

- ^ Patrick C. Y. Woo, Yi Huang e Susanna K. P. Lau, Coronavirus Genomics and Bioinformatics Analysis, in Viruses, vol. 2, n. 8, 24 agosto 2010, pp. 1804-1820, DOI:10.3390/v2081803, ISSN 1999-4915, PMID 21994708.«Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (Pol) of coronaviruses with complete genome sequences available. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method and rooted using Breda virus polyprotein.»

- ^ Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis, in Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 1282, Springer, 2015, pp. 1-23, DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1, ISBN 978-1-4939-2438-7, PMID 25720466.«See Table 1.»

- ^ Susanna K. P. Lau, Paul Lee, Alan K. L. Tsang, Cyril C. Y. Yip,1 Herman Tse, Rodney A. Lee, Lok-Yee So, Yu-Lung Lau, Kwok-Hung Chan, Patrick C. Y. Woo, and Kwok-Yung Yuen. Molecular Epidemiology of Human Coronavirus OC43 Reveals Evolution of Different Genotypes over Time and Recent Emergence of a Novel Genotype due to Natural Recombination. J Virology. 2011 November; 85(21): 11325–11337.

- ^ E. R. Gaunt,1 A. Hardie,2 E. C. J. Claas,3 P. Simmonds,1 and K. E. Templeton. Epidemiology and Clinical Presentations of the Four Human Coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43 Detected over 3 Years Using a Novel Multiplex Real-Time PCR Method down-pointing small open triangle. J Clin Microbiol. 2010 August; 48(8): 2940–2947.

- ^ Fields, B. N., D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.). 1996. Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA.

- ^ Hoek, L. van der, P. Krzysztof, and B. Berkhout. 2006. Human coronavirus NL63, a new respiratory virus. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30:760–773. [PubMed]

- ^ A Rare Case of Human Coronavirus 229E Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in a Healthy Adult. Vassilara F, Spyridaki A, Pothitos G, Deliveliotou A, Papadopoulos A. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2018 Apr 15;2018:6796839. doi: 10.1155/2018/6796839. eCollection 2018. PMID 29850307 Free PMC Article

- ^ Pene, F., A. Merlat, A. Vabret, F. Rozenberg, A. Buzyn, F. Dreyfus, A. Cariou, F. Freymuth, and P. Lebon. 2003. Coronavirus 229E related pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:929–932. [PubMed]

- ^ Vabret, A., T. Mourez, S. Gouarin, J. Petitjean, and F. Freymuth. 2003. An outbreak of coronavirus OC43 respiratory infection in Normandy, France. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:985–989. [PubMed]

- ^ Woo, P. C. Y., S. K. P. Lau, H. Tsoi, Y. Huang, R. W. S. Poon, C. M. Chu, R. A. Lee, W. K. Luk, G. K. M. Wong, B. H. L. Wong, V. C. C. Cheng, B. S. F. Tang, A. K. L. Wu, R. W. H. Yung, H. Chen, Y. Guan, K. H. Chan, and K. Y. Yuen. 2005. Clinical and molecular epidemiological features of coronavirus HKU1 associated community acquired pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 192:1898–1907. [PubMed]

- ^ Esper, F., C. Weibel, D. Ferguson, M. L. Landry, and J. S. Kahn. 2006. Coronavirus HKU1 infection in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:775–779. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- ^ Gerna, G., E. Percivalle, A. Sarasini, G. Campanini, A. Piralla, F. Rovida, E. Genini, A. Marchi, and F. Baldanti. 2007. Human respiratory coronavirus HKU1 versus other coronavirus infections in Italian hospitalised patients. J. Clin. Virol. 38:244–250. [PubMed]

- ^ Kaye, H. S., H. B. Marsh, and W. R. Dowdle. 1971. Seroepidemiologic survey of coronavirus (strain OC 43) related infections in a children's population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 94:43–49. [PubMed]